DestinAsian Magazine: Hungry for Hue

Journalist, Content Creator, Copy Writer, PR & Media Consultant, WSJ, VOGUE, Food & Wine, Conde Nast Traveller, Departures, WWD, AD

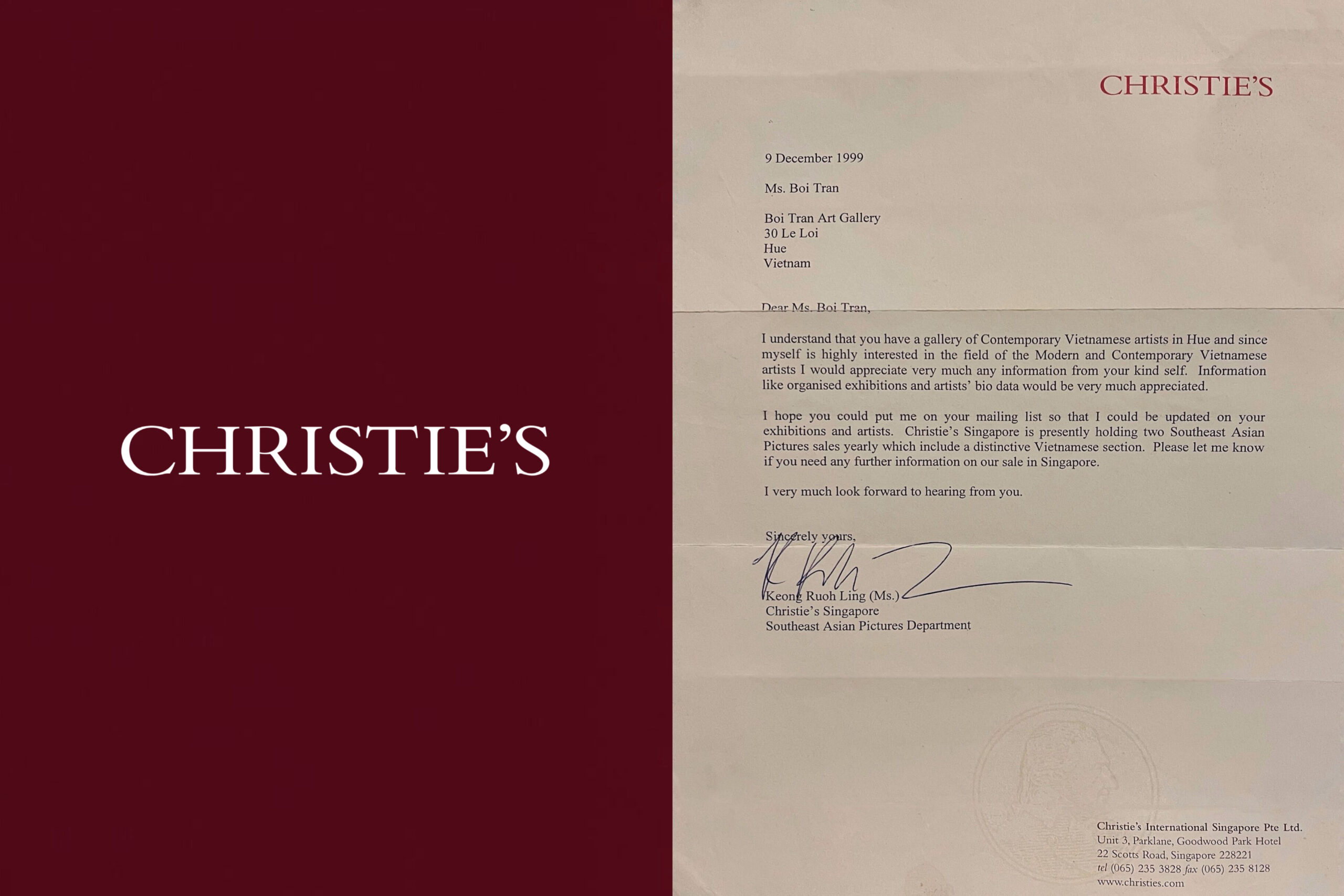

Many of the old culinary traditions live on, and today, Hue cuisine is held to be Vietnam’s most delicious and diverse. A visit to Ancient Hue, a home restaurant and gallery of an eccentric, elegant artist and chef Boi Tran, gives visitors an inkling of what a royal banquet and a meal crafted according to the Phong Thuỷ (Feng Shui) ideals of balance — five elements, five colours, five tastes might have been like.

Famed for both its elaborate courtly cuisine and the humbler fare of its streets, Vietnam’s former imperial capital beckons with some of the most tantalizing cooking in the country.

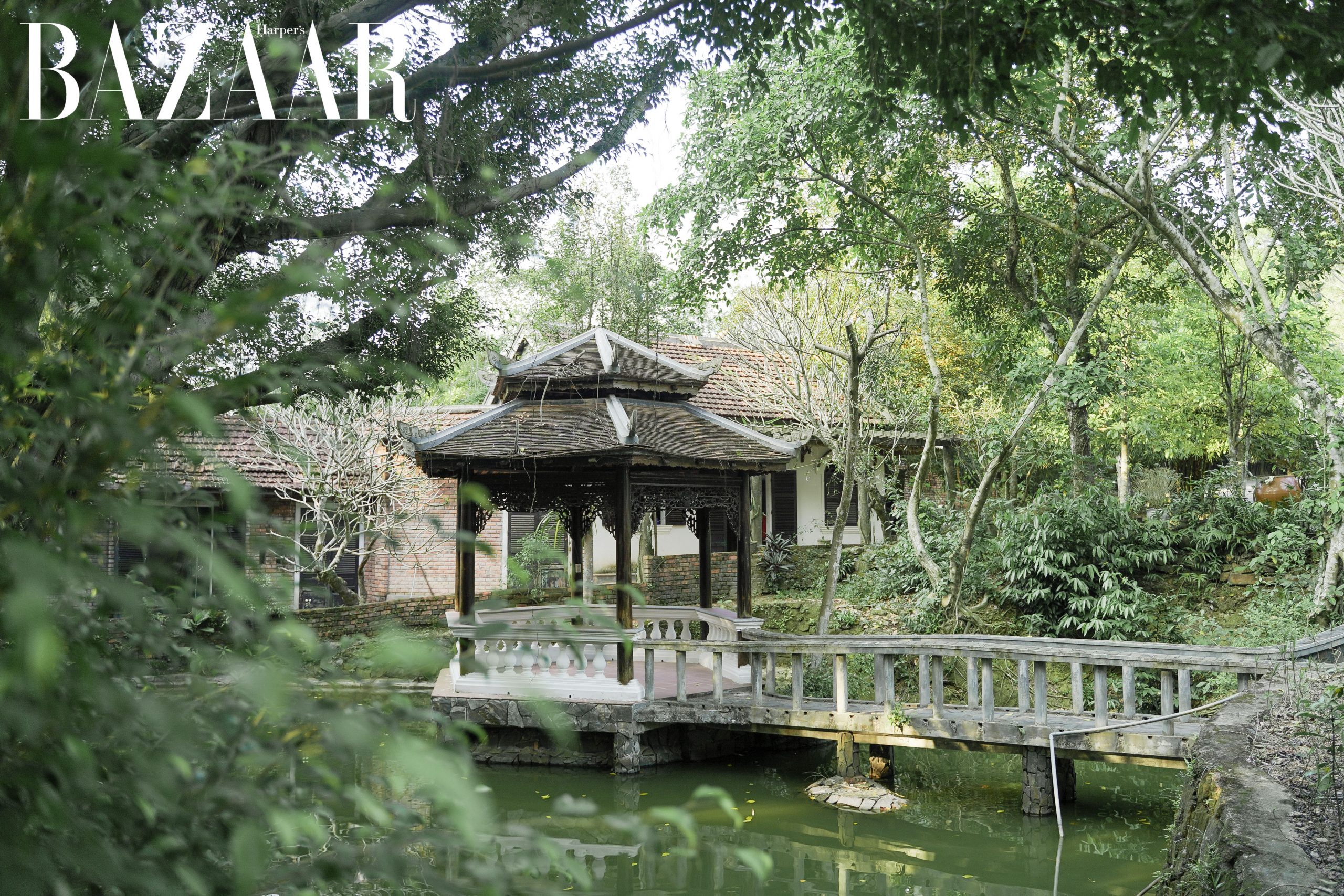

The Nguyen kinds might be long gone, but in Hue, the legacy of Vietnam’s last royal court lingers. Compared with the frenzied pace of development in Ho Chi Minh, this historic UNESCO-listed town on the central coast is peaceful, slow-paced, and inescapably charming; on my first morning, I watched schoolgirls in pastel-coloured Áo dài bicycle through towering stone ramparts on their way to class, and wiry cyclo drivers padel piles of fresh fruits and vegetables to market along the moat of the Citadel, commissioned in 1804 by Emperor Gia Long as the seat of his new capital.

Under Hue’s imperial rule, all aspects of Vietnamese culture, from art to architecture, were adapted and refined. The cuisine was no exception. The country’s most celebrated chefs were brought to the city, where they developed thousands of new recipes. According to court chronicles, it was not uncommon for a lavish banquet to feature 300 different dishes, each — like old Hue itself — a perfect balance of colour and composition.

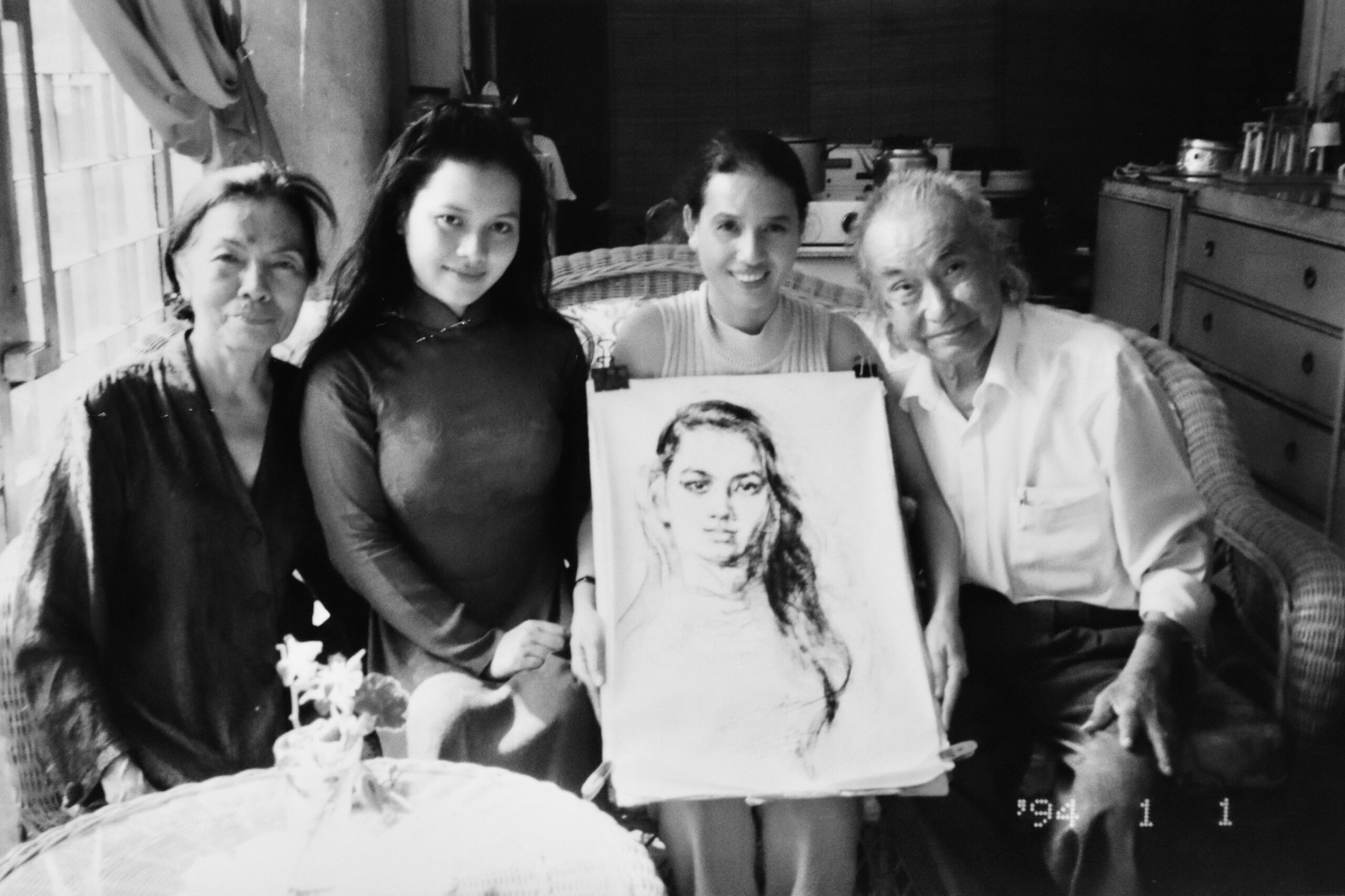

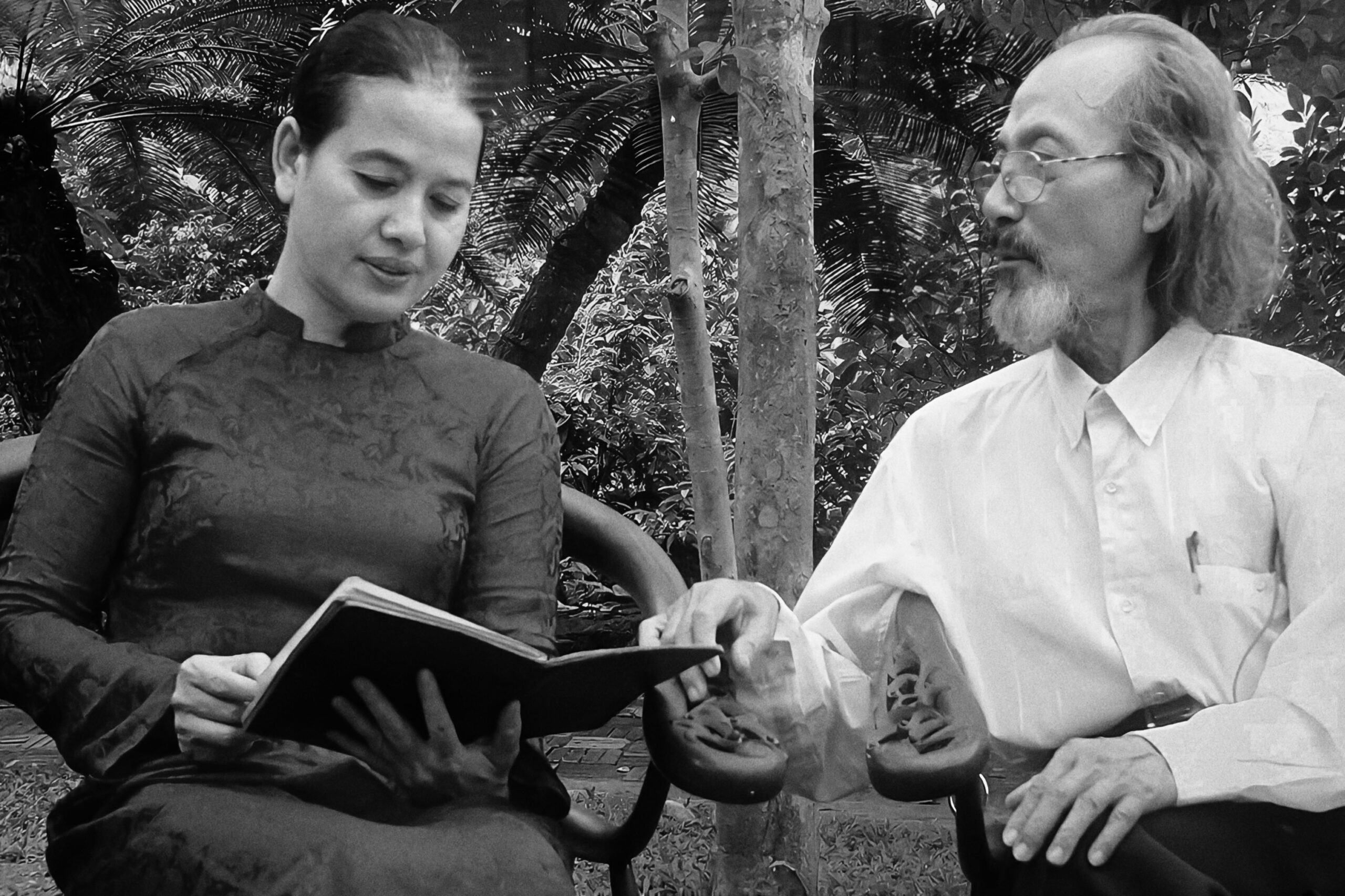

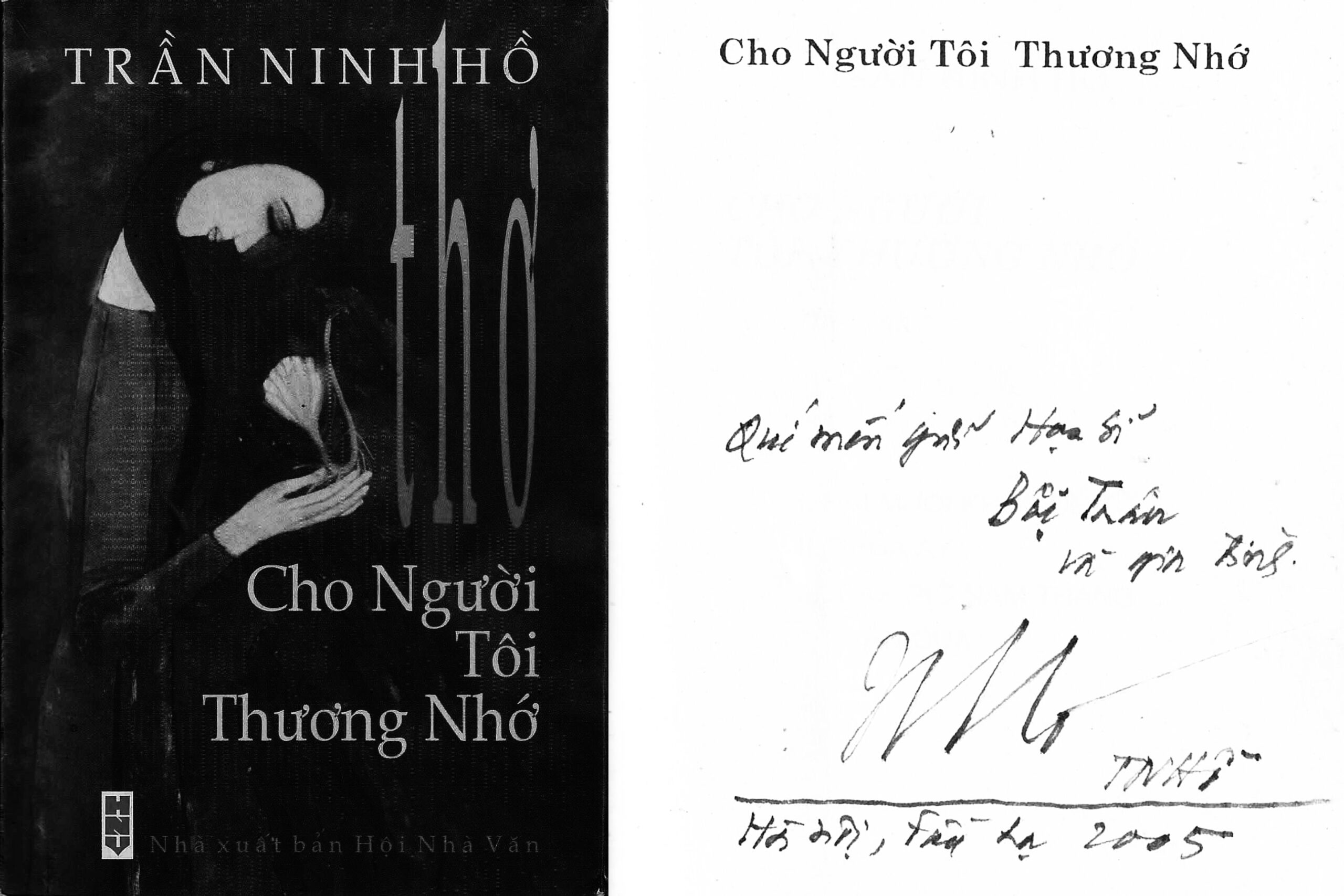

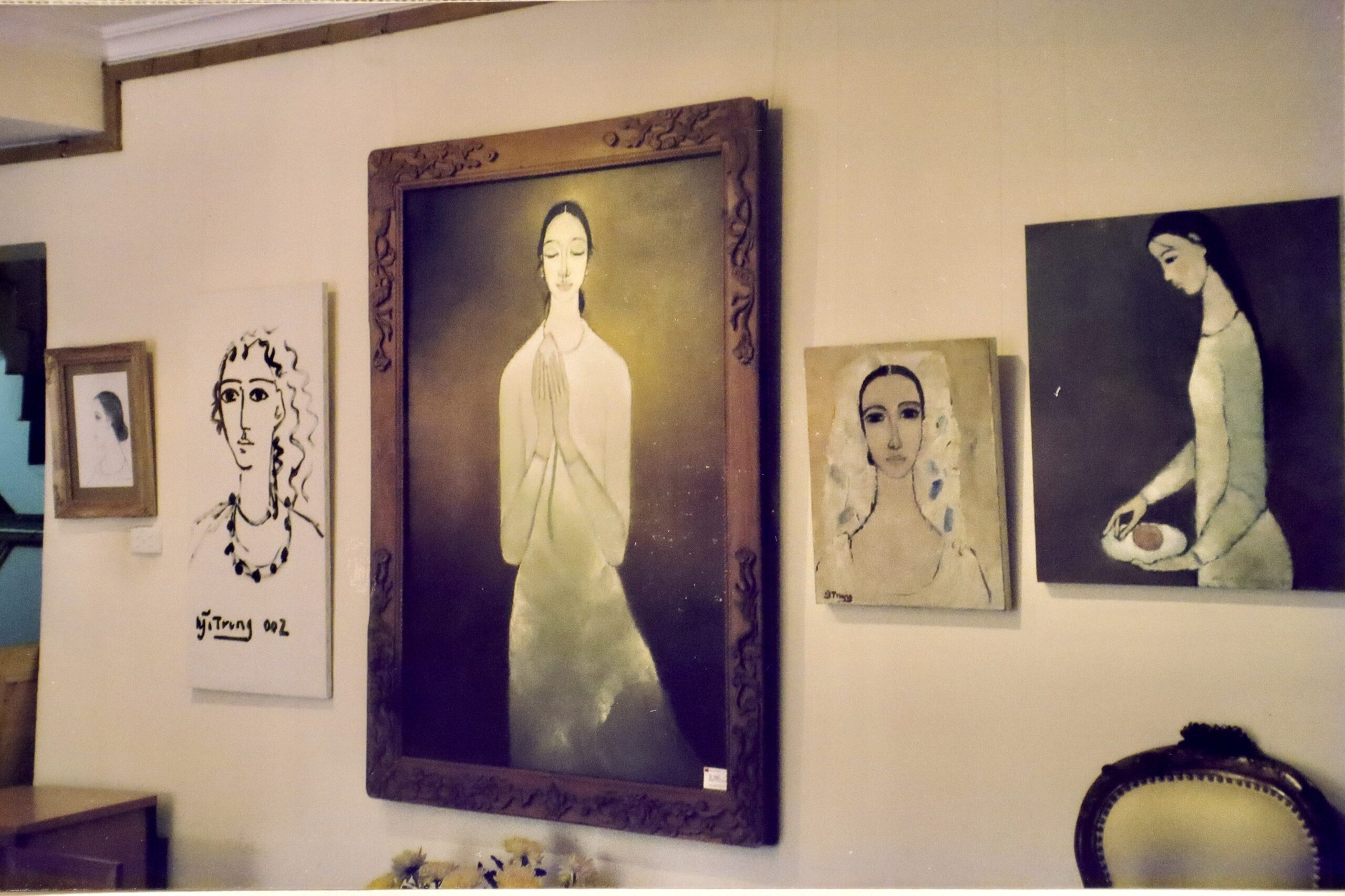

Many of the old culinary traditions live on, and today, Hue cuisine is held to be Vietnam’s most delicious and diverse. A visit to Ancient Hue, a home restaurant and gallery of an eccentric, elegant artist and chef Boi Tran, gives visitors an inkling of what a royal banquet and a meal crafted according to the Phong Thuỷ (feng shui) ideals of balance — five elements, five colours, five tastes might have been like. Her wooden Hmong minority house is set along a winding hillside track outside town, and when not catering to guests, she spends most of her days painting in her studio or garden. I sat chatting with her at a long wooden table while a feast carefully calibrated to the damp March weather was laid upon the green silk runner.

To start, a single, succulent shrimp served with “five tastes” (Tôm Ngũ Vị) in a clear broth spiced with lemongrass, shallots, chilli, lime leaf, and ginger; then a deliciously warming beef consommé accompanied by a steamed rice paper roll secured with dainty pandan-leaf bows. Following this was a fig salad (Vả Trộn), made with fruit from her garden, and her father’s favourite: red-rice soup with the bống fish.

“Slow cooking is a signature of Hue dishes,” Boi Tran explains “For instance, this soup takes 24 hours to make: the rice must be cooked all night long, and the fish stewed with sugar for three or four hours, stirring continuously. It was a favourite of the Nguyen Kings.”

Emperor Gia Long‘s decision to build his capital at the confluence of rivers, seas, mountains, flood plains, and lagoons ensured that his subjects and their descendants would not want food in any season, whether the chilly winter or the searing summer. During the cool days of spring, stallholders do a roaring trade in vegetables, beans, eggplants, pumpkins, and root vegetables, all nourished by the rains and nutrient-rich deposits from the Perfume River.

Source Destinasian.com