A Fork in Asia’s Road: The Hue Home by John Krich

PEN/Hemingway Award Novelist

Former Asian Wall Street Journal Food & Arts Columnist; Travel Writer, Critic, Feature Writer, Journalist

The generator that lights Boi Tran’s garden goes out in the midst of the first course — a frequent occurrence along this remote hillside on the road to forested royal tombs. From the outdoor table, stars can be seen peeking through the trees. Yet it seems a special shame to dig in without first having a look at dishes designed by this cultured city’s most renowned artist — and one of the remarkable women who have used their homes to help revive their hometown’s food culture.

Vietnamese know Hue, the last imperial seat of Vietnam, as a culinary capital. But look in Lonely Planet and it directs you to two grungy balconies overlooking city ramparts still pocked with American and Vietcong bullets, where some old guy in a T-shirt may or may not be moved to bring out stale egg rolls congealed in grease. Travellers in this newly awakened provincial town often have to settle for the indifferent, generic fare at massive riverfront eateries or package-tour replications of “imperial” settings. On side streets, there are the better-preserved remnants of royal snacks in the form of tiny saucers of steamed rice-flour pancakes topped with various garnishes of garlic and dried shrimp. But much of the time, visitors are left in the dark.

For me, it’s only an accident: the generator that lights Boi Tran’s garden goes out in the midst of the first course — a frequent occurrence along this remote hillside on the road to forested royal tombs. From the outdoor table, stars can be seen peeking through the trees. Yet it seems a special shame to dig in without first having a look at dishes designed by this cultured city’s most renowned artist — and one of several remarkable women who have used their homes to help revive their hometown’s food culture.

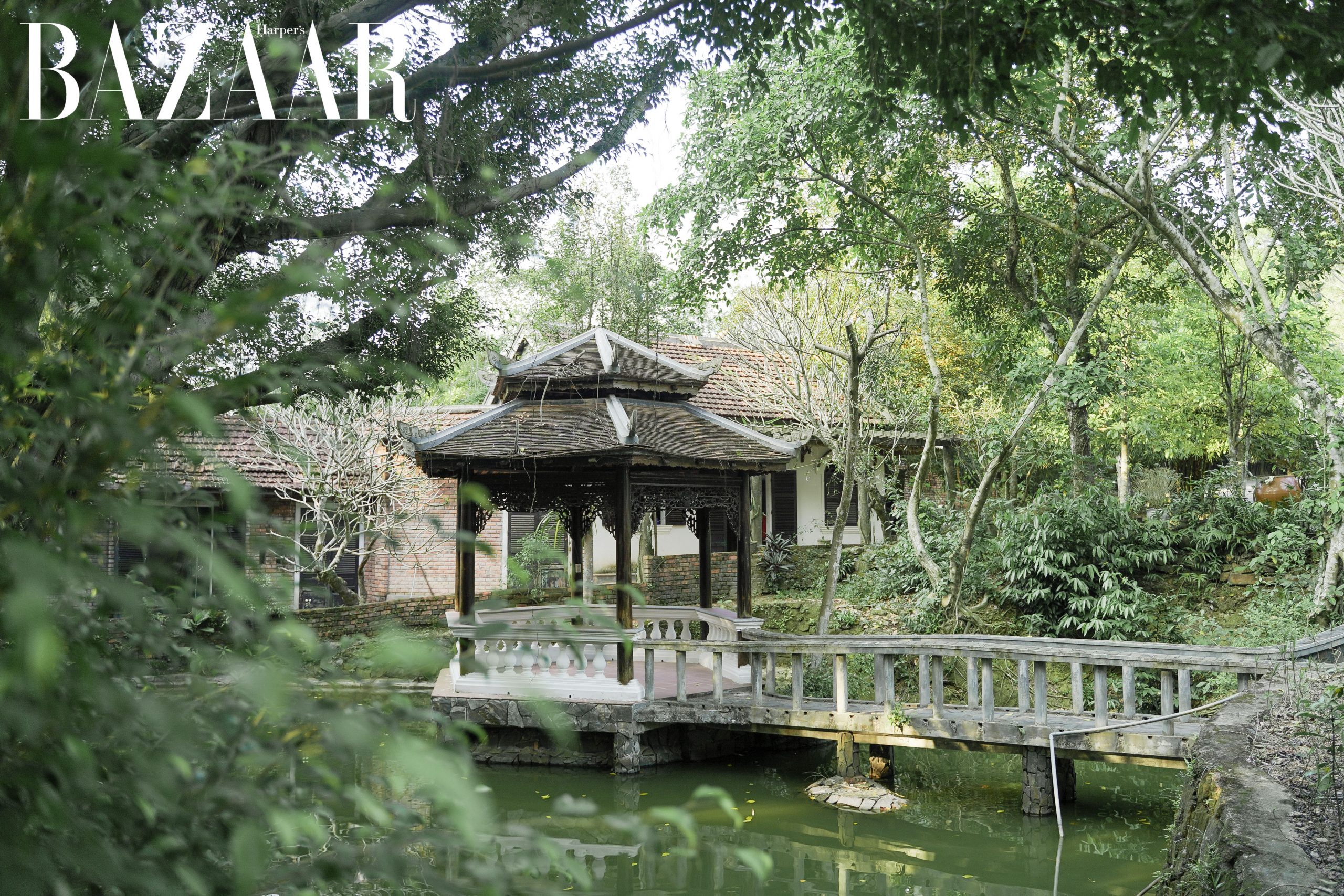

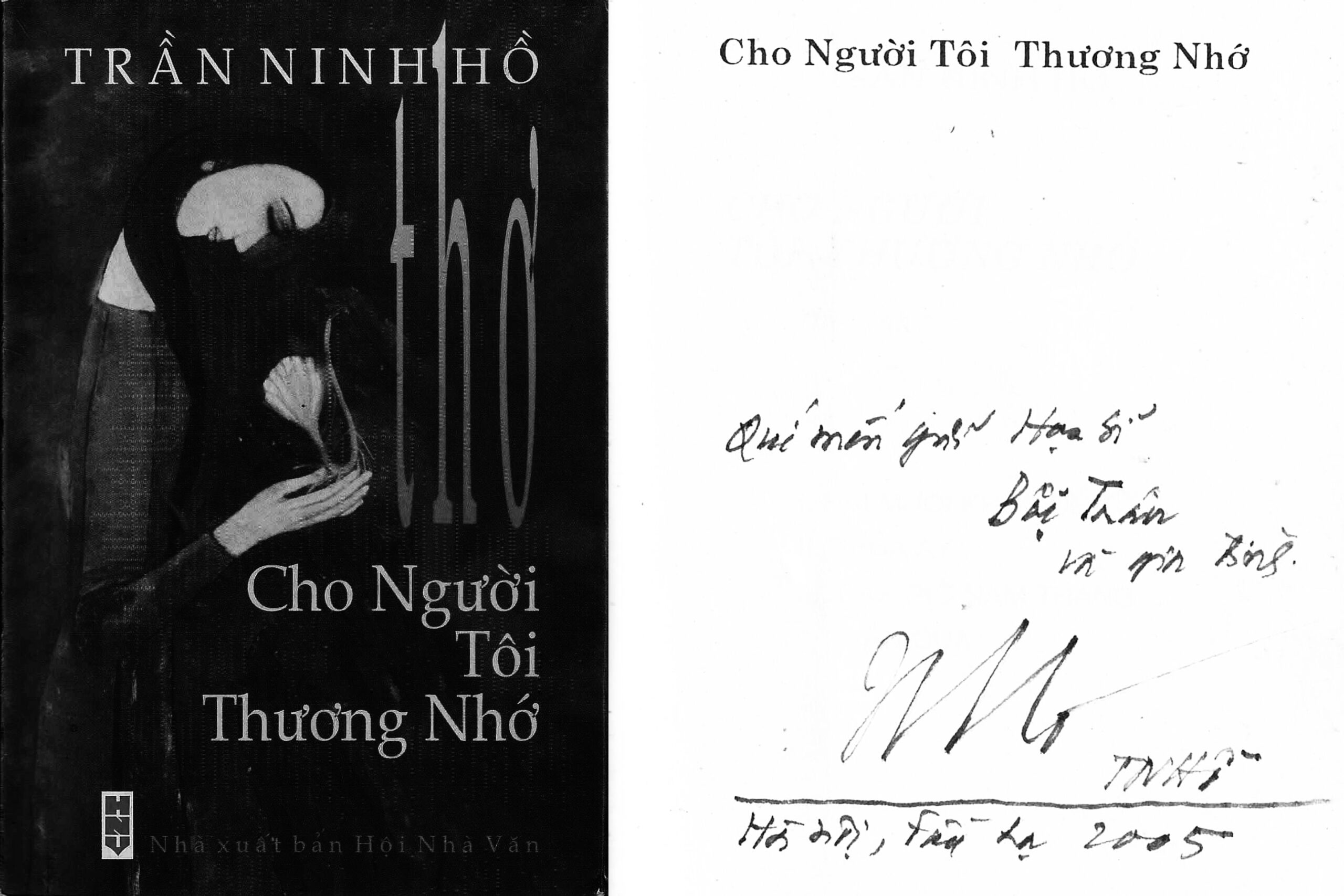

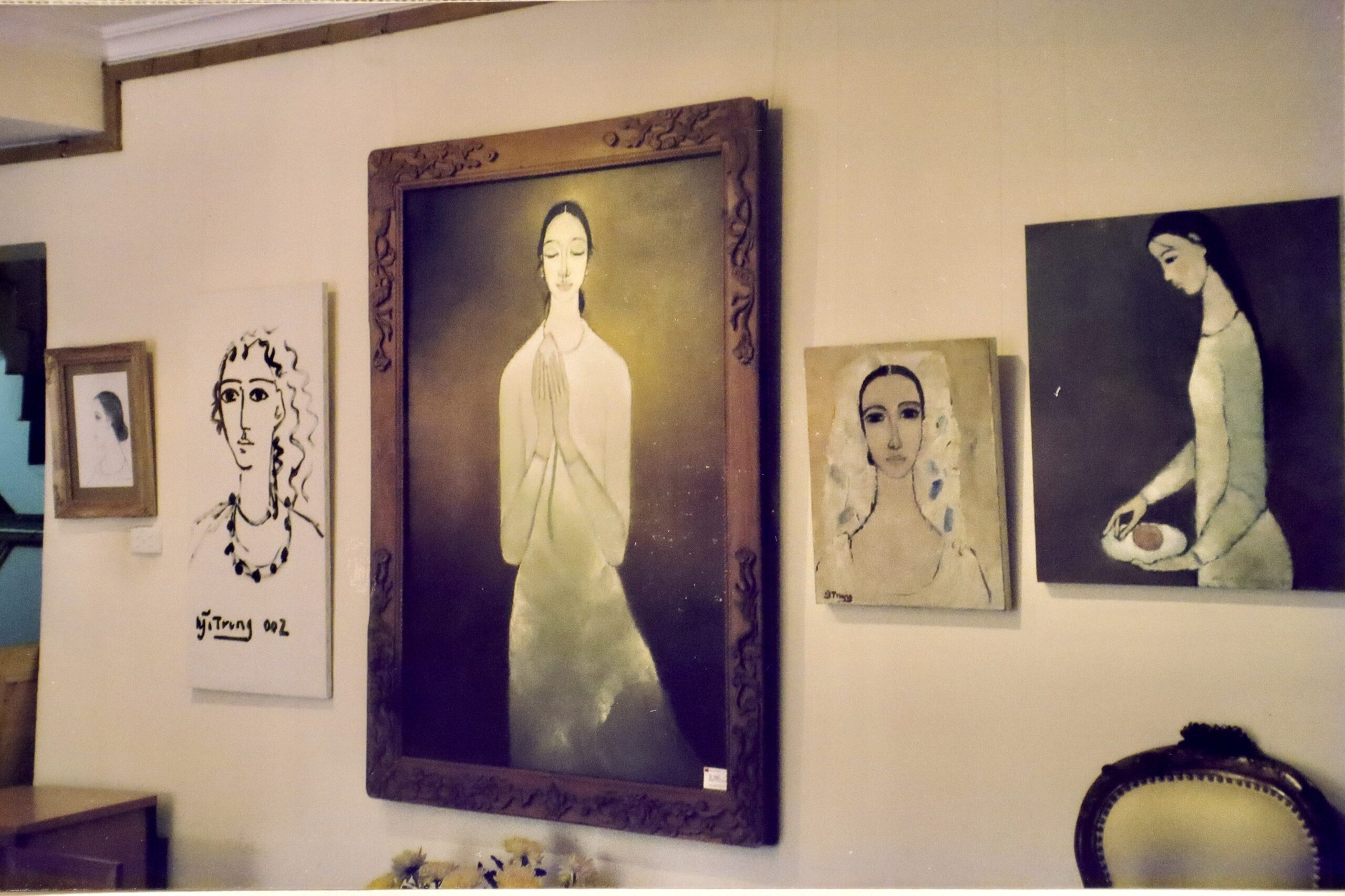

There are stacks of delicate “paper rolls” meant to be dipped in a thick beef mélange; vả trộn, a special local fig minced with spices to taste like raw fish; and a circular, soup-floated display of whole shrimp “in five tastes.” These seem to complement the rest of Boi Tran’s creations, sumptuous canvases of mysterious women and landscapes that have made her one of Vietnam’s highest-priced painters — viewed by pre-dinner daylight in the large oblong gallery that fronts her landscaped compound of fruit trees, lotus ponds and traditional tribal houses, where for the past decade she has worked and cooked

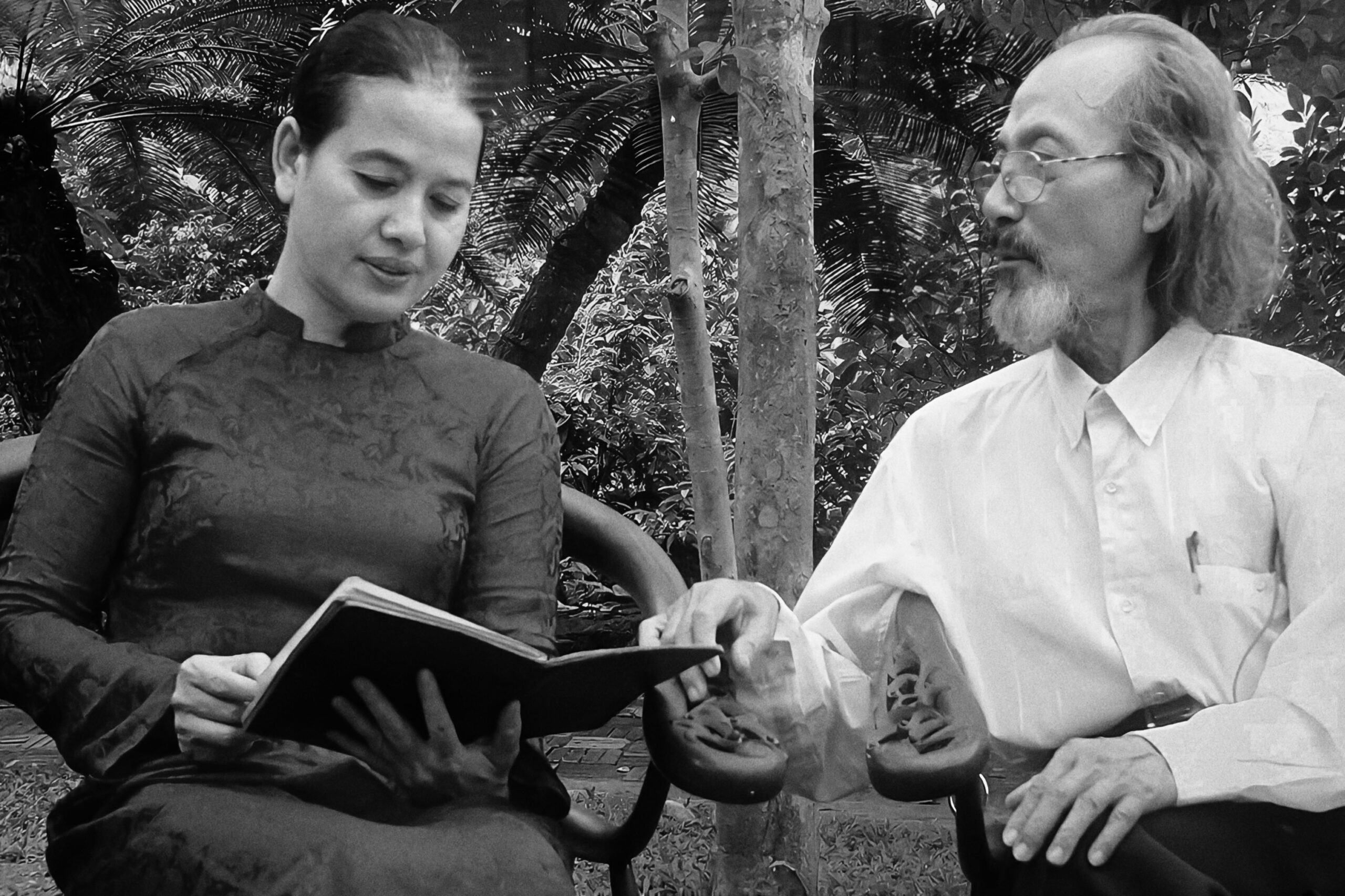

“At first, I made meals only for friends,” says this imposing woman, still strikingly attractive at 53 in her traditional silk ao dai, yet self-possessed as a modern executive. “Then visitors and groups kept making requests — and for me this is an extension of my pride, to keep alive the true Hue taste and feeling.”

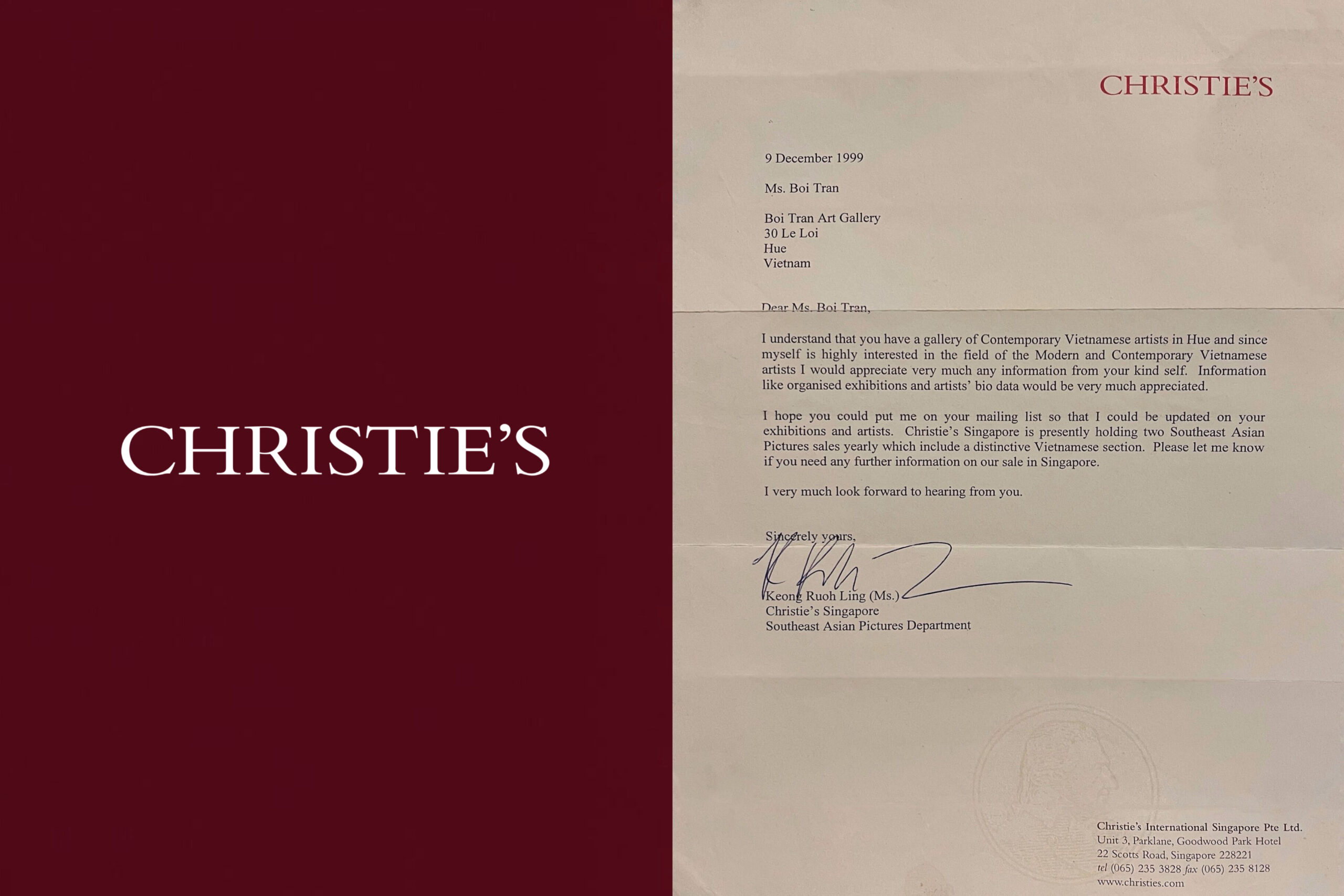

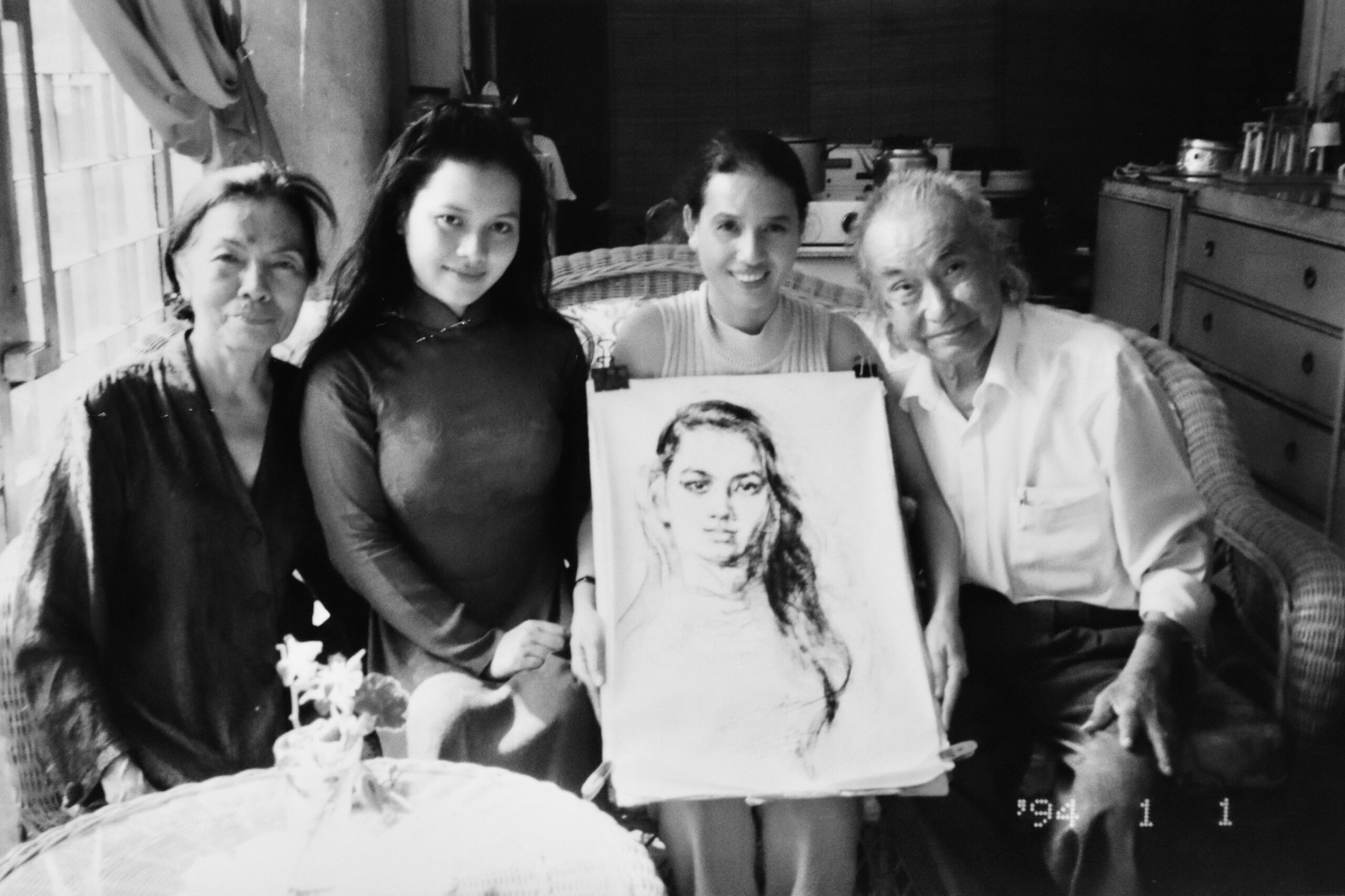

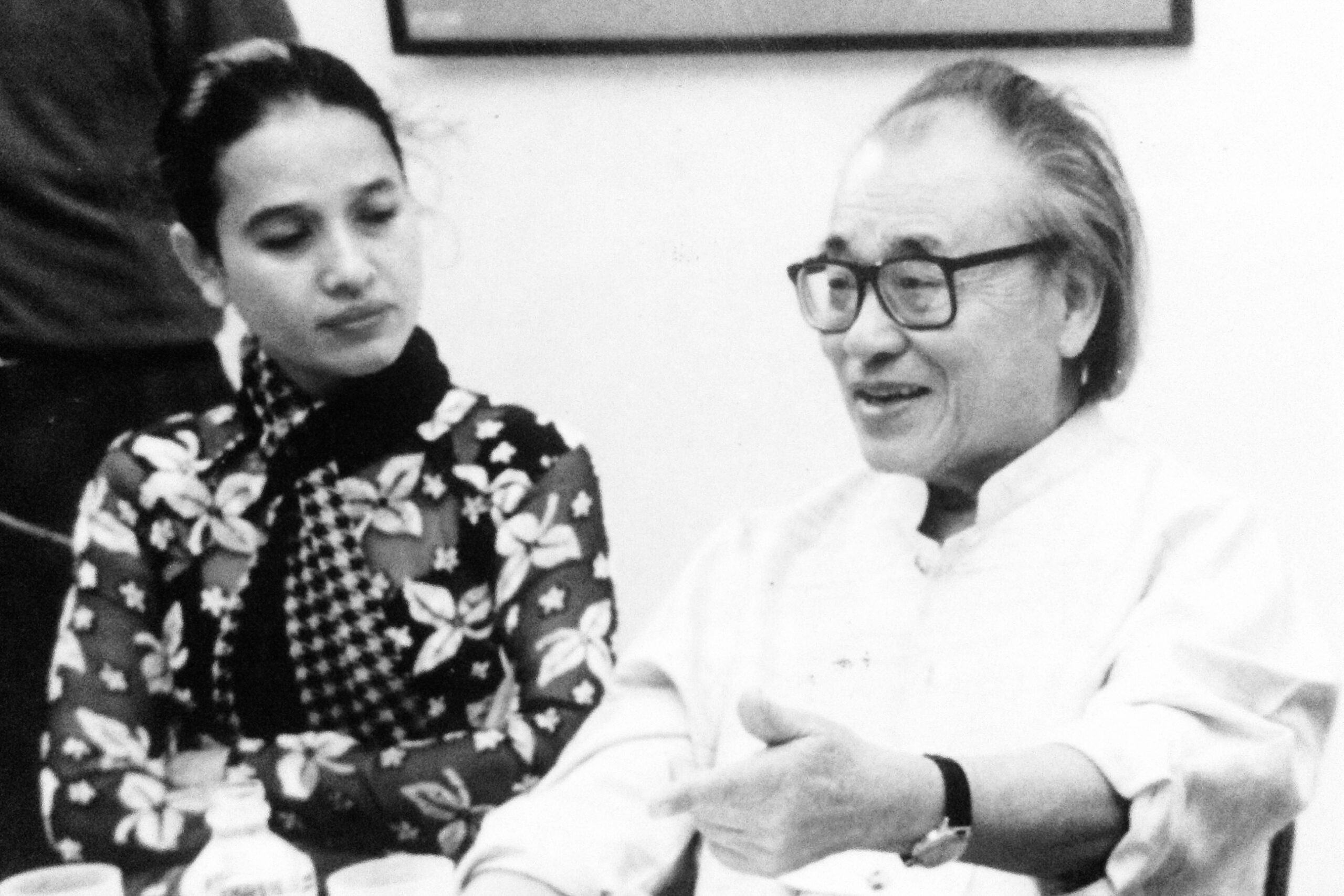

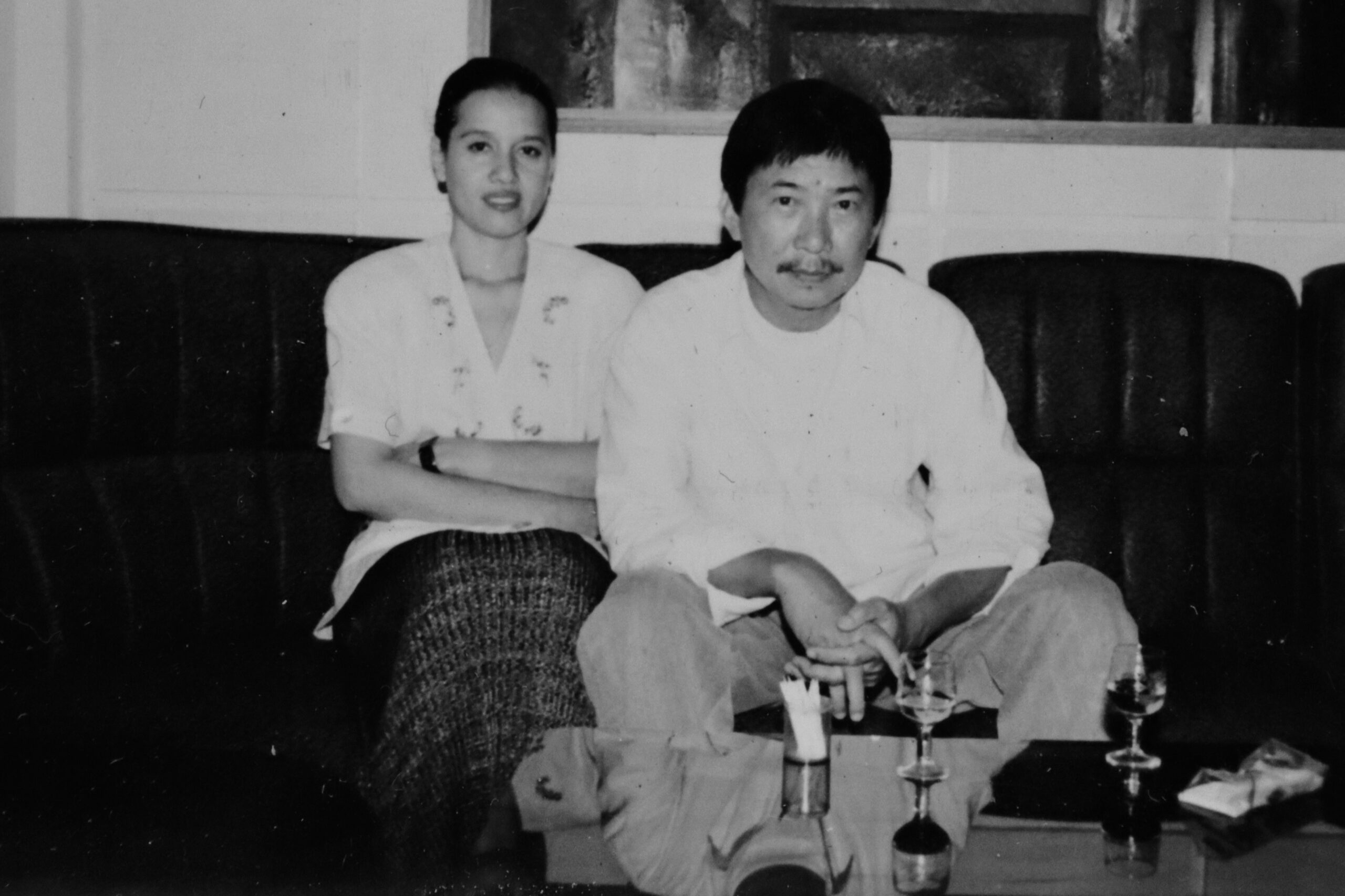

In this, she would seem to know what she is talking about, as she traces generations of ancestors having lived in Hue since 1380. But Ms Tran’s biography is hardly typical of Vietnamese women. Divorced in 1987 from a wealthy businessman who moved to the U.S. two decades back, she always loved to paint and studied under some of Vietnam’s modern masters in Ho Chi Minh City. She may have become willing to open her home regularly and serve as the city’s kind of unofficial hostess for important foreigners to quell some of her loneliness. The largest, and most beautiful, wooden structure in her garden, is, ironically lined with photographs of her beloved son and a shrine to his memory. He died at age 22 in a 2002 California swimming accident while trying to save a friend.

With little outward show of emotion, she admits that she has often cooked banquets honouring his spirit. She decided to build and create her studio and retreat, never planning it as a restaurant, in 1999. Motivated in part to have an in-town place for both cooking and socializing, but mainly to spearhead the restoration of an especially beloved nhà rường (Hue-style wooden altar house), she quietly opened Hoang Vien (“Royal Garden”) in March this year. While clearly a restaurant, its two symmetrical dining pavilions and outdoor courtyard seem more like extensions of Boi Tran’s life and art.

The food, too, is a somewhat standardized version of Tran’s family favourites — but good enough to make this the classiest and most consistent restaurant within the ancient Hue city walls. On the menu are especially delicate renditions of green jackfruit salad, ginger cuttlefish, and rice with lotus seeds. There’s a decent wine selection, even sashimi of garoupa with mustard sauce for a fusion touch. “But Hue food has to be delicate, in small dishes — even the rice servings are small,” Boi Tran explains.

Back in her garden on a Saturday morning, Boi Tran instructs a trusty kitchen staff in making a special breakfast of extra-wet and delicate snacks of dried shrimps in banana leaf and rice pancakes. She also welcomes guests by preparing rare teas in a highly ceremonial manner that like much else here is claimed as the essence of Vietnamese yet decidedly Chinese. While she could be at her easel or resting on her laurels, Boi Tran scouts coastal villages for special fish sauces hits the markets for the most seasonal produce and, she boasts, would never add MSG. “People thought I was crazy at first,” this most dedicated of Hue women says with a sigh. “But this is the only way to renew our country.”